In Praise Of Decontrol: Part Two, cont.

Decontrol helps make TIMN’s four contradictory forms become compatible

I initially figured I could write about decontrol without having to recap TIMN. But it remains so unfamiliar that, the more I tried to write succinctly, the more I sensed I better explain. So, here comes some recapping to provide context. If it doesn’t work for you (my writing style is admittedly bulkier than ever), go give my overview blogpost a read (Ronfeldt,2009), or at least browse its summary charts and diagrams. Speaking of which, what’s below is not entirely a recap — it includes a new diagram I’ve meant to add for years. I hope it helps….

• Recap of TIMN’s Elements: Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks

The TIMN framework springs from my sensing in the late 1980s that the digital information technology revolution would favor network forms of organization. At the time I was writing up an idea that Cyberocracy Is Coming (Ronfeldt, 1993) and had no intention to work on social evolution. But I began wondering what other forms of organization societies had relied on across the ages, besides networks. Hierarchies and markets were two, I soon learned. Then I spotted that hierarchies (I preferred the term institutions), markets, and information-age networks could be viewed as an evolutionary progression, arising one after the other. After assembling them initially in an institutions + markets + networks (IMN) framework (Ronfeldt, 1993), I felt something was missing— there had to be an earlier form. Further research taught me that tribes preceded the other forms. Satisfied, I added tribes and assembled all four forms into the framework I’m using here, acronymed TIMN (Ronfeldt, 1996).

TIMN’s four cardinal forms: According to TIMN, people assemble into societies so they can live better by living and working together. This began millennia ago, and along the way people repeatedly turned to four cardinal forms of organization for staying together and getting things done:

The kinship-based tribe, as denoted by the structures of extended families, clans, and other lineage and affinity systems.

The hierarchical institution, as exemplified by states, armies, and other corporate enterprises, including the Papacy.

The competitive-exchange market, as symbolized by merchants and traders responding to forces of supply and demand.

The collaborative network, as found today in the web-like ties among some NGOs devoted to social advocacy.

The development of each form has a long history. Incipient versions of all four were present in ancient times; they have co-existed since people first began to assemble into societies — someone was always doing something using one or more of those forms of interaction and organization.

But as formal societal designs with philosophical portent, each has gained strength at a different rate and matured in a different epoch over the past 10,000 or so years. Tribes rose first (in the Neolithic era), with civil society becoming its modern manifestation. Millennia later, hierarchical institutions developed next, resulting in such exemplars as the Roman Empire, the Papacy, and then the absolutist states of the 16th century. Centuries later, competitive market systems emerged, as in England and the United States during the 18th-19th centuries. Hence we have our modern societies with their three major realms: civil society + government + market economy.

If that were the end of the story, people’s prospects for evolving still more complex societies would be nearing an evolutionary cul-de-sac per the “end of history” argument. However, the network form is now coming into its own, starting a few decades ago. Collaborative information-age networks are on the rise as the fourth cardinal form of organization, governance, and evolution, as seen mainly among activist nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) so far but elsewhere too.

Network forms have been around, in use, for millennia. But they lacked the right information and communications technologies to enable them to take hold and spread. Indeed, each preceding form emerged, in turn, because an enabling information revolution occurred at the time: speech and storytelling for tribes, writing and printing for institutions, telegraphy and telephony for markets. The digital information technology revolution is what’s energizing the network form, enabling it to compete with the other forms and address problems they are proving unable to resolve adequately.

More than mere forms: Each of TIMN’s four forms, writ large, embodies a distinctive set of structures, processes, beliefs, and dynamics about how society should be organized — about who gets to achieve what, why, and how. Each emphasizes different values, codes, and standards about how people should treat each other. Each has different strengths and limitations. Each enables people to do something — to address some problem — better than they could by using another form. Each attracts and energizes different kinds of actors and adherents. Each has different ideational and material bases. Each has both bright and dark sides, both strengths and weaknesses. And each can be gotten “right” or “wrong” in various ways, depending on circumstances.

Thus, once a form is subscribed to by many actors, it becomes more than a mere form: It develops into a system of thought and action. Indeed, the rise of each form spells an ideational and structural revolution. Each thus generates social energy and order, for each defines specialized interactions (or transactions) that are attractive, powerful, and useful enough to lead to the creation of a distinct separate realm of activities. Each becomes the basis for a governance system that is self-regulating and, ultimately, self-limiting. And each tends to foster a different kind of worldview, for each orients people differently toward social space, social time, and social action. What is deemed rational — how a “rational actor” should think and behave — is different for each form; no single “utility function” suits them all. Political philosophers, social theorists, and ideologues of all sorts eventually tend to seize on emphasizing one or another of the forms, and then to argue vigorously with proponents of one or another of the other forms, as in today’s debates over whether governments or markets are the solution.

Even though each form becomes associated with high ideals as well as new capabilities, they are all ethically neutral — as neutral as technologies — in that they have both bright and dark sides and may be used for good or ill. The tribal form, which should foster communal solidarity and mutual caring, may also breed a narrow us-vs.-them tribalism that can justify anything from nepotism to murder in order to shield and strengthen a clannish group and its leaders. The hierarchical institutional form, which is supposed to lead to professional rule and regulation, may also serve to uphold corrupt arbitrary dictators. The market form, which should bring open free fair exchange, may also be rigged to allow unbridled piracy, speculation, and profiteering. And the network form, which can empower civil-society actors to serve public interests, may also be used to strengthen “uncivil society” actors — for example, by enabling transnational terrorist groups and crime syndicates. So, it is not just the bright sides of each form that foster new values and actors; their dark sides may do so as well.” (adapted from Ronfeldt, February 2009)

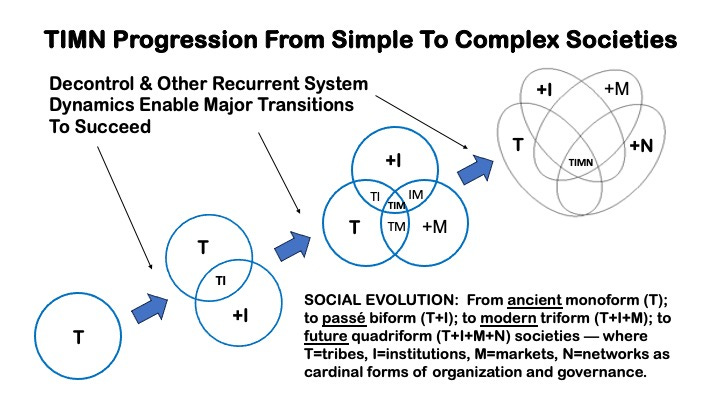

The TIMN progression: Across history, then, evolutionary progress is about societies learning to develop and combine these four cardinal forms of organization, emphasizing their bright sides while controlling their dark sides. Not everyone has benefitted along the way. But overall, this evolutionary arc — from tribe-centric, to hierarchy-centric, to market-centric, and potentially next to network-centric systems — has enabled most societies to perform better, so that people can live better.

In doing so, societies have advanced in complexity from ancient monoform (T-only), to passé biform (T+I), to modern triform (T+I+M) designs. Along the way, the tribal form morphed into what we now call civil society, the institutional form into the modern bureaucratic state, and the market form into the capitalist economy — making civil society, government, and market economy into the three grand realms of all modern societies. In the decades ahead, America’s future depends on progressing from today’s triform design to a next-generation quadriform T+I+M+N) design with four realms: civil society + government + market economy + a new yet-to-unfold realm.

As a set of Venn diagrams, that progression looks like this:

In looking at that depiction, remember it covers some 10,000 years of social evolution, during which T stands initially for the ancient tribal form, then for its modern manifestation as the realm of civil society. The +I realm consists primarily government and its public sector(s), and the +M realm mainly of the market economy and its private sector(s). The +N realm will become the future network-based realm that TIMN predicts will emerge, and for which there is currently little evidence.

Reflecting real life, this depiction shows all forms and realms overlapping and interacting in various combinations. Mono-, bi-, and triform societies are easy to depict with circles. Circles are also widely used by people to depict four elements of one kind or another all interacting. But in fact using circles for four or more elements is an error — a couple of possible overlaps will be always missing. To assure that all possible overlaps and intersections appear when depicting four our more elements, ellipses must be used. Hence my odd unfamiliar diagram for a future quadriform society. (For clarification, go here: https://www.mydraw.com/templates-venn-diagram)

This depiction of TIMN is idealized; it’s mainly for discussion purposes. The way it’s laid out above may describe a few actual societies, but not many. The way to treat the depiction so it can apply to essentially all societies is to make it flexible and variable. For example, to represent an autocratic society make the +I circle bigger relative to T and +M. For a society with a centralized statist economy, diminish +M. For a corrupt society, enlarge T and increase its overlap with +I if the corruption is largely political, with +M if it’s largely economic, since most corruption stems from the penetration of old tribal dynamics into modern sectors of a society.

There are also other ways to make this kind of Venn diagram more accurate. And there are other ways to depict TIMN that I hope to field someday. For now, however, I shall have to hope this sketchy depiction helps make the point that, as a framework, TIMN’s fundamentals are simple: four cardinal forms of organization that emerge at different rates in different historical eras, plus a set of system dynamics, including decontrol, that recur when a new form emerges and gains hold. But as details are added, this seeming simplicity allows for sufficient flexibility, variability, and complexity to be informative and predictive in ways I’ve not seen in other evolutionary frameworks.

Decontrol as a crucial system dynamic: With that set of diagrams and the preceding discussion in mind, it should make sense that achieving these progressions in complexity is no easy feat. For the TIMN forms are quite different from each other. As ideals, they fundamentally contradict each other. In many ways, they are incompatible, tug in different directions, and are difficult to combine and hard to harmonize. Yet no society at any scale can do without them — all of them, to some degree. Thus during each phase transition there are major winners and losers. Operational challenges and power struggles occur all along the way, with many turning on issues of what to control and what to decontrol.

Evolutionary decontrol (not to mention control too) may be seen, then, as an art and science of creating a modus vivendi among the forms. Which means finding ways to harmonize their contradictions so their interactions become compatible and productive. Achieving a mutually-adaptive compatibility between the forms and their realms may be the defining goal of decontrol (not to mention control too).

One way to accomplish that over time is by respecting each form’s strengths and limitations, the better to keep them in balance and within limits in their respective realms and sectors. TIMN apparently has policy biases embedded within its evolutionary dynamics, and one is about keeping the forms and their realms in balance and within their design limits. Which I hope you’ll come to see as a social problem that generally requires decontrol as well as control measures. Which I’ll try to clarify further in the next section by recapping TIMN’s dozen or so system dynamics.

References

David Ronfeldt, “Overview of social evolution (past, present, and future) in TIMN terms,” Materials for Two Theories, Blog, February 25, 2009, posted online at:

http://twotheories.blogspot.com/2009/02/overview-of-social-evolution-past.html

. . . . . . .

Please stay tuned: continuations on this decontrol topic will appear sooner or later, depending….

The same goes for posts on other topics I’ve been writing up for months: notably, “Two Civilization-States At Odds” (about a way to improve U.S.-China dialogue by emphasizing noopolitics rather than geopolitics); and “Global Great-Power Netwar II” (about America currently being under systematic cognitive attack from Russia and related Far-Right networks using social netwar strategies and tactics that Putin and his strategists believe the West used against it to win the Cold War and weaken Russia).

Great post, Dave. Question- what would you need to see to say that the Quadriform has arrived on the scene? We've seen networked movements arise on the world stage (Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, MAGA, etc), but are you saying they aren't enduring enough forms as of yet? I wonder how the return of Guilds for various disciplines plays into this.