Rethinking What “Tribes” and “Networks” Are Good For (Part I)

Networks For Hugging Inward vs. Networks For Reaching Outward

Sometimes it takes years for a simple “of course” idea to surface. This one’s been on the verge the whole time. Finally it popped up a month or so ago. I still have doubts and questions, but it appears to be a significant improvement in how to look at TIMN’s four forms: Tribes + Institutions + Markets + Networks. It has new implications for analyzing what’s going on and finding a way forward.

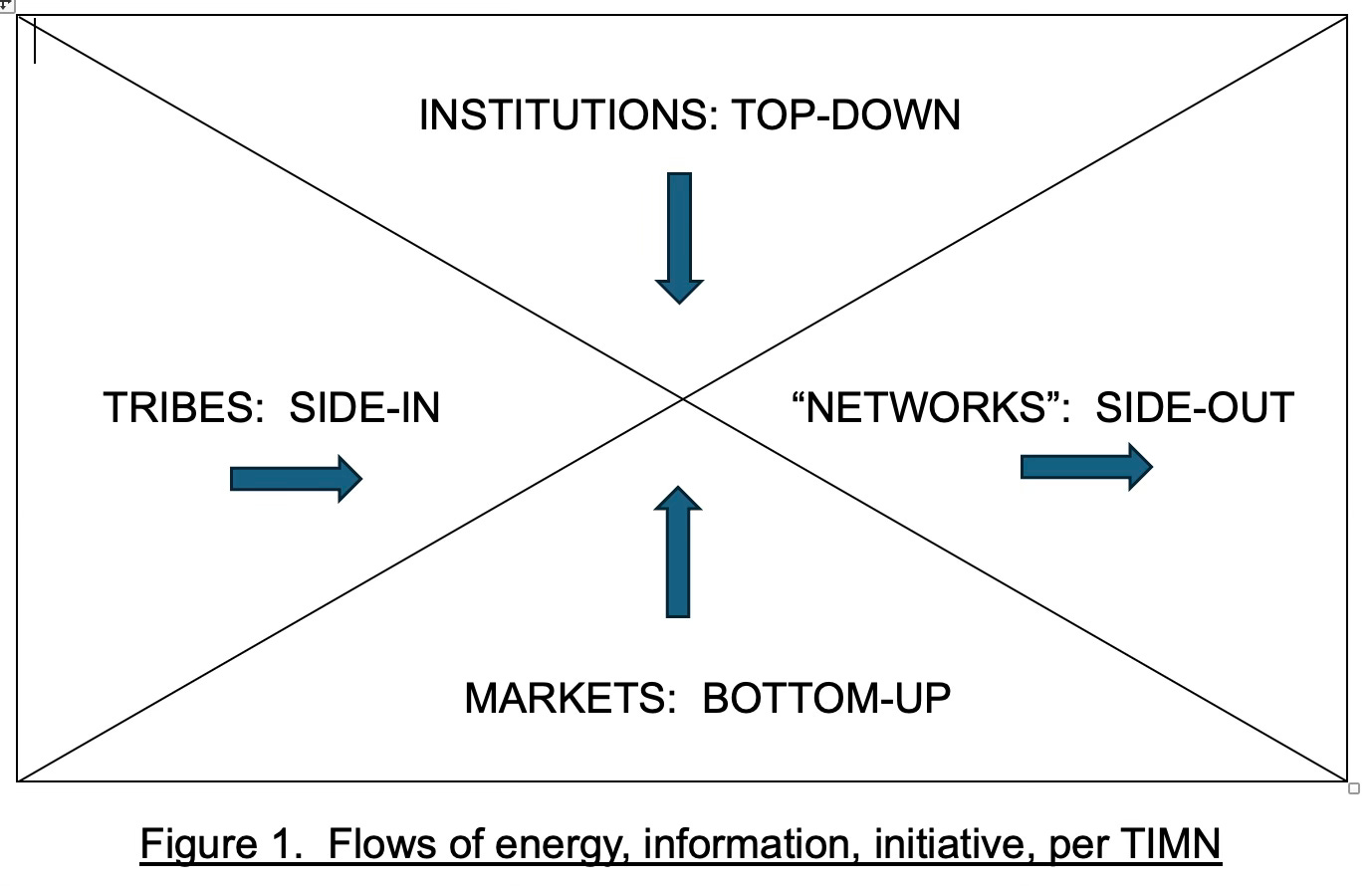

In brief, the idea is to rethink TIMN’s four forms in terms of whether their impulses (energies, momentums, motivations) flow primarily top-down, bottom-up, side-in, or side-out. Viewing Institutions as top-down and Markets as bottom-up is quite common. My new insight is to equate TIMN’s Tribes and Networks forms with sideways impulses — Tribes with hugging people inward to bond a group together, Networks with reaching outward to collaborate with outside groups and organizations elsewhere.

This refinement is helping me understand TIMN better. I hope it helps you as well. If not, at least I’ve now logged the idea.

I’ve also come up with a visual representation. Figure 1 previews how the four forms tend to function this way in a society:

That figure shows where this post is headed. As usual. it’s a theoretical post, full of dry language. But I’ve also come up with an idyllic landscape image for viewing Figure 1. And it’s not so dry. Nor necessarily idyllic. Keep it in mind as we go along. I do more with it in Part III.

o Look at how Tribe’s in-reaching and Network’s out-reaching arrows flow left-to-right. Think of that flow as a long wide river (or highway) of people moving left-to-right, at first in separate tribal clusters, then in larger formations we call civil society, finally in various still-larger more-networked formations reaching out to people in other societies.

o Now think of Institution’s top-down area in Figure 1 as a towering mountain range in the background beyond the river. And Market’s bottom-up area as an enormous valley full of activity in the foreground this side of the river.

o Put all that imagery together and we have a dynamic panorama that metaphorically matches my updated take on TIMN. Visually, we see a “long march of humanity” moving from primitive to pro-planetary formations along the river, smoothly in places but with eddies and undercurrents along the way. We can also see that what occurs in the mountains and valleys — where I’ve placed state institutions and market economies — may affect what happens along that river, for better and worse. Likewise, disturbances along the river/road may spill into +I’s mountains and +M’s valleys.

o More to the point — my newest point — perturbations along the river may be seen to cause oscillations between the more tribalized and more networked formations that define the river’s flow toward the future, sometimes resulting in reversions to the dark sides of the Tribes form, yet always promising eventual advances for the +Networks form. Thus the T and +N formations stand in oscillation as well as contradiction to each other, much as do the +Institutions and +Market forms. All TIMN possibilities — from harmonious progress to regressive collapse — coexist in this metaphorically dynamic landscape view.

I’ll explain more later. But first a recap of how I got there, which I’d advise skipping if you’re already familiar with the ABCs of TIMN.

RECAP OF MY PAST DEPICTIONS OF TIMN’S FORMS

My work on long-range societal evolution sprang from finding that societies have long depended on using four major forms of organization: kinship-based tribes + hierarchy-based institutions + exchange-based markets + collaboration-based networks — hence the acronym TIMN. Accordingly, these four fundamental forms of organization and interaction have existed as “seed forms” since the beginning. Soon as people began assembling into small societies thousands of years ago, somebody was always doing something that used, and depended on using, one or more of these four forms, be it as individuals or in small groups.

As history progressed — as people needed to do more and more together — these seed-forms were put in use so widely and systematically that they grew into realm-defining forms of organization and belief. Each gets used, in turn, by particular actors to address particular problems in ways that developed into formalized realms (sectors, spheres, systems) of society.

This did not happen all at once. Each form came into its own in a different historical era in a spread-out progression. The Tribes form arose first, the Institutions form next, etc. — as I’ve recounted many times before.

I’ve made several efforts to compare TIMN’s four forms and their distinctive attributes, replete with sketchy charts and wordy tables. First in my original paper on Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework About Societal Evolution (1996). Later in a follow-up titled In Search Of How Societies Work: Tribes — The First and Forever Form (2006). Then, after I retired, in blog posts, notably “Overview of social evolution (past, present, and future) in TIMN terms” (2009), and “Organizational forms compared: my evolving TIMN table vs. other analysts’ tables — revised & expanded” (2016). (I’ve been collecting new materials for years to update that 2016 table, but it’s not happened yet.)

Those efforts have been informative, but they all beg for improvements too. Figuring out the Networks form has perplexed me the most. But my new reformulation should help.

NEW POINTS ABOUT THE “TRIBES” AND “NETWORKS” FORMS

As I and others have long said, the Institutions form tends to be top-down, the Markets form bottom-up. For +I is about using hierarchy, power, authority, law, collective endeavor, etc. to impose order and spur progress. In contrast, +M is about letting liberty, freedom, innovation, self-expression, individual initiative, etc. energize progress. The two forms amount to contradictory opposites, even though societies need both and must work to make their operations compatible.

But what about the Tribes and Networks forms? If they’re not bottom-up or top-down, then what are they?

As the first form to take hold in ancient times, Tribes is about emphasizing inter-personal kinship, lineage, identity, solidarity, community, sharing, etc. to form a close-knit society. In contrast, information-age Networks is ideally about reaching out to others while emphasizing openness, inclusion, collaboration, etc. in flat network designs.

That’s been evident about the Tribes and Networks forms since I unearthed the TIMN framework. Yet I’ve never had neat spatial referents for them like we have for Institutions (top-down) and Markets (bottom-up). Nor have I considered T and +N as polar opposites — contrasts yes, but not paradigmatic opposites.

All that has changed in recent weeks. Three points I’ve long had in mind finally gelled together, prompting a new take on the T and N forms. Those three points are:

Sideways energies matter as much as top-down and bottom-up:

Comparisons are often made about something that is said to operate top-down, versus something else that seems bottom-up — long the case with hierarchies vs. markets. Yet forces and factors are rarely said to operate from the side, the middle, or the center. Top-down vs. bottom-up analyses always attract attention. Middle-, center-, and side-in (or -out) comparisons rarely appear. But the more I think about it, that’s what T and +I mainly are: forms that reach and operate sideways — Tribes quite inwardly and locally since ancient times, Networks quite expansively as suits the information age. That’s one clarification that’s dawned on me.

External impulses behind each form’s rise increase over time:

The TIMN framework rests not only on its four cardinal forms, but also on a dozen or so system dynamics that recur during every major transition in the progressions from past monoform (T-only) to future quadriform (T+I+M+N) societies. One of those recurrent system dynamics is that each form’s rise involves broader geographic forces and factors than did its predecessor. As the T+I+M+N progression unfolds, the impulses to push for a form’s emergence arise, each time in turn, from a more expansive set of actors, energized by interests in a more expansive geography.

Thus the Tribes form initially has the narrowest demographic scope of all the TIMN forms — just the small number of families, clans, and approved outsiders who constitute a tribe. Moreover, an early tribe’s geographic focus may be limited to nearby fields, valleys, rivers, and ranges. The later evolution of the Institutions form involved much larger geographic territories and populations — e.g., principalities, kingdoms, states, empires. Evolution of the Markets form involved still more distant geographies and populations — not just national but also transnational, and beyond. By extrapolation, the impulses for advancing the Networks form, though they may originate in specific locales, will stem from nearly global if not planetary matters.

Lately, as a corollary, I’ve noticed that the impetus behind each form’s rise comes not only from a geographically more expansive set of actors, but that the set’s constituency has an ever-larger external component. The outside (foreign) component increases with each step in the TIMN progression. Though I can’t be sure, a growing foreign component may be essential for each form in turn to gain sufficient impetus to emerge and take hold within a society.

Accordingly, early Tribes formed for strictly local reasons, with few to no outsiders involved, partly to prevent outside influences. The evolution of +I involved farther-ranging impulses, including dynastic intermarriages. With the evolution of +M, the proportion of domestic to foreign impulses became about even, I’d surmise, since foreign commerce, banking, and investment increasingly impelled societies’ domestic actors to base their economies on market (+M) more than personal (T-type) or statist (I-type) principles. By extrapolation, the impulses for a society to evolve a +N realm (whatever that may consist of) may stem more from external than internal dynamics.

“Networks” is becoming too vague a concept to suit TIMN:

Identifying Networks as TIMN’s fourth and future form of organization was a favorite reason for fielding TIMN back in the early 1990s. The form was just taking off, thanks to the digital information revolution. Few other analysts had spotted its rise back then. And at the time it seemed a distinctive form of organization, different from TIMN’s first three forms: Tribes, Institutions, and Markets.

But naming the fourth form “Networks,” though still accurate and pertinent, doesn’t help as much anymore. Partly that’s because the new field known as “network science” took off in the 1990s-2000s too — only to classify all forms of organization as varieties of networks, including TIMN’s tribes, hierarchies, and markets. Networks turned into a trendy bandied word in both research and policy circles. Lots of efforts then went into analyzing and advising how to improve existing social and organizational networks — but not into specifying innovative network designs that may be needed in the future. All of which raised questions and took some edge off my TIMN usage.

Moreover, based on personal experience, there’s often somebody around who turns to deflate ideas that something new is on the way. In this case, they’d point out that networks are not new, far from it — kinship networks, road networks, trade networks, etc. have existed since ancient times. Which is true. And maybe they didn’t mean to be dismissive. But such comments tend to re-direct discussion away from figuring out the future toward reflecting on the past. I often groan and turn mum at that point.

That said, it’s still unclear exactly what network designs will be needed to structure the +N realm that TIMN augurs. If my deduction is correct, it’ll be a pro-commons realm that encompasses health, education, welfare, and environmental matters But today’s cutting-edge ideas about networks — e.g., “decentralized autonomous organizations” (DAOs), “distributed cooperative organizations” (DisCOs), “open value networks” (OVNs), holacracy, holarchy, and the like — look insufficient for scaling upwards, downwards, and sideways to structure a new realm. Something grander, bigger in scale, more interconnectable across “silos,” perhaps “cosmo-local,” looks needed. And its functionality — top to bottom and side-to-side across all issue areas — may be manageable only if Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) systems are brought in.

Such a vast networks-based realm-defining design doesn’t exist yet, nor do components for beginning to assemble it. It lacks a name too. But I’ve wondered whether “equinets” or “exonets” might be more accurate than plain “networks” — meaning the acronym TIMN would aptly become TIME.

Though I’m not ready to insist on it yet, the term “ exonets” is appealing, for it expresses both the key commonality and key difference I’ve lately found regarding the Tribes and Networks forms: to wit, they are both based on networks — they are both network-centric forms, far more so than are the Institutions and Markets forms. Tribes and Networks are fundamentally different, however. The Tribes form results from kinship and other social-identity networks meant to bond and bind people together as an in-group — Tribes function primarily inward. In contrast, the Networks form reaches primarily outward — it functions to connect and coordinate professional purpose-driven actors irrespective of Tribes identities. The two forms are related (and interrelated), but they cannot substitute for each other. Their strengths and weaknesses are different.

I’ll continue to elaborate on these differences and draw implications for theory and strategy in Parts II and III. Today I realized my draft about this reformulation had become too long and unwieldly for a single blog post. So I’m issuing it as a three-part post. Don’t give up before I reiterate Fig 1, and start telling you about the dual axes of oscillation and pulsation I’ve unearthed in TIMN’s innards.

TO BE CONTINUED

REFERENCES

Ronfeldt, David, Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework About Societal Evolution, RAND Corporation, 1996, online at:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P7967.html

Ronfeldt, David, In Search Of How Societies Work: Tribes — The First and Forever Form, RAND Corporation, 2006, online at:

https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR433.html

Ronfeldt, David, “Overview of social evolution (past, present, and future) in TIMN terms,”Materials for Two Theories, (old personal blog), 2009, online at:

https://twotheories.blogspot.com/2009/02/overview-of-social-evolution-past.html

Ronfeldt, David, “Organizational forms compared: my evolving TIMN table vs. other analysts’ tables — revised & expanded,” Materials for Two Theories, (old personal blog), 2016, online at:

https://twotheories.blogspot.com/2016/05/organizational-forms-compared-my.html

CODA: A LITTLE NIGHTCAP MUSIC

Since I used a river metaphor above, here are two gems in that frame, the first fitting my use of that metaphor, the second more fitting for sipping a Scotch nightcap:

Brian Eno – Asian River – 1988

www.youtube.com/watch?v=cXDOVR-r7cc

Julie London – Cry Me A River – 1955